This has been a topic I’ve wanted to write about for a while. And now I finally have the time and patience to start.

Introduction

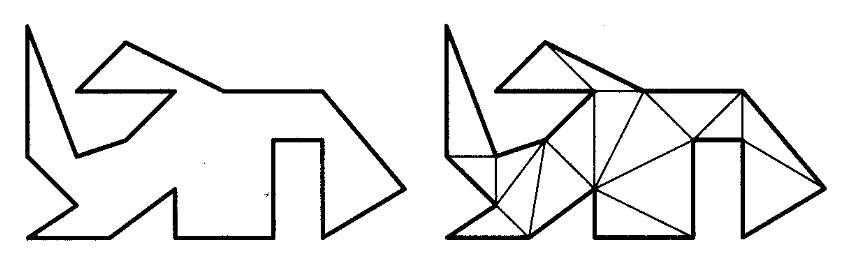

Polygon triangulation is the partition of a polygon into a set of triangles. Since polygons are pretty hard to deal with, splitting a polygon into simpler components via polygon triangulation can allow us to solve some problems more easily. These problems include the art gallery problem, and finding the shortest distance between two points inside a simple polygon.

The simplest recursive approach to triangulating a polygon will run in $O(N^3)$. Using the ear clipping method, it is possible to lower this time complexity to $O(N^2)$. Of course, it is possible to triangulate a polygon in $O(NlogN)$, which is the algorithm I will be explaining in this post. In addition, a very complex $O(N)$ algorithm for polygon triangulation has been found, and a more practical $O(Nlog^*N)$ (in practice, indistinguishable from linear) algorithm exists as well.

Now, lets get into the algorithm.

The Algorithm Overview

The algorithm relies on two facts. First, a polygon can be decomposed into monotone polygons in $O(NlogN)$. Second, a monotone polygon can be triangulated in $O(N)$ ($O(NlogN)$ if you include sorting). In other words, the algorithm has two steps:

- Decompose the polygon into monotone polygons

- Triangulate each monotone polygon

Just in case you don’t know, a monotone polygon refers to a polygon where for some line $L$, the number of intersection points between a line orthogonal to $L$ and the polygon is less than or equal to 2. In this algorithm, the given line is the $y$-axis. In other words, the monotone pieces we create will have up to two intersection points with a line parallel to the $x$-axis.

Next, lets look at each step with more detail.

Part 1 - Decomposition into Monotone Polygons

Explanation

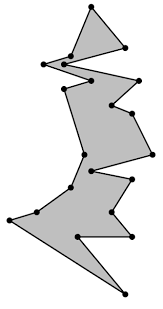

To decompose a polygon into monotone polygons, we must first divide the polygons vertices into one of five groups. More specifically, each vertex in the polygon will be either a start, end, regular, split, or merge vertices.

Seeing the image above will give you a rough idea of what each type of vertex means. A start vertex is a vertex where its $y$-coordinate is larger than the $y$-coordinate of its two adjacent vertices, and the inner angle is less than $180^{\circ}$. An end vertex is the opposite, where the two adjacent vertices have a higher $y$-coordinate and the inner angle is less than $180^{\circ}$. A regular vertex is a vertex whose $y$-coordinate is in between the $y$-coordinate of its two adjacent vertices. A split vertex is like a start vertex, but the inner angle is larger than $180^{\circ}$. Finally, a merge vertex is like an end vertex, but the inner angle is larger than $180^{\circ}$. Using these properties, it is possible to determine the type of all vertices in $O(N)$.

One thing we can know from dividing the vertices into groups, is that if a polygon has no split or merge vertices, it is monotone. This can be proven, but I’ll talk about it later. Because of this, we can add edges in the polygon to remove split and merge vertices, therefore making the polygon monotone. We are going to achieve this by sweeping from top to bottom, and adding an edge whenever we meet a split or merge vertex.

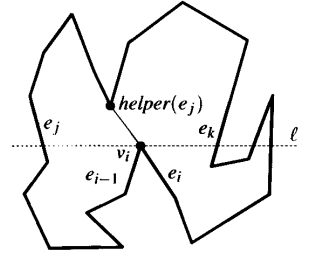

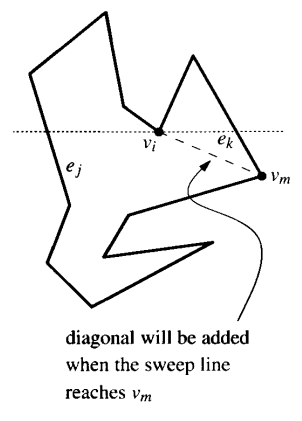

Then how would we add edges? Lets start by handling split vertices. Assume $v_i$ is a split vertex. It would be a good idea to connect $v_i$ to a vertex close to it, since it would be less likely the edge intersects the polygon. Precisely, lets call $e_j$ the edge to the immediate left of $v_i$ on the sweep line, and $e_k$ the one on the immediate right. Then, we can always connect $v_i$ to the lowest vertex in between $e_j$ and $e_k$, and if there are none, connect it to the upper endpoint of $e_j$ or $e_k$. This vertex is called the helper vertex of $e_j$, and we’ll denote it as $helper(e_j)$. Formally, $helper(e_j)$ as the lowest vertex above the sweep line where the horizontal segment connecting the vertex and $e_j$ is within the polygon.

So that’s how we deal with split vertices. Then what about merge vertices? This seems difficult because we have to connect it to a vertex that we have not yet visited. Thankfully, it is not much harder. Like before, lets assume $v_i$ is a merge vertex and $e_j$, $e_k$ are the edges on the left and right of $v_i$. First, we can see that when we visit $v_i$, it will become the new helper vertex of $e_j$. Also, we want to connect $v_i$ to the highest vertex between $e_j$ and $e_k$ that is below the sweep line, which is the opposite of what we did for split vertices. We can’t know what this vertex is, as we did not visit it yet, but we can find out later on. When we meet a vertex $v_m$ that becomes the new helper of $e_j$, we can check if the previous helper was a merge vertex, and if so, add an edge between $v_i$ and $v_m$. If there is no vertex to further replace $helper(e_j)$, we just connect it to the lower endpoint of $e_j$.

Now, we can construct a full algorithm for the decomposition.

The Algorithm

Let $P$ be the polygon. Also, let $T$ be a data structure that stores edges, and makes it possible to find an edge directly left to a vertex. I will give a more detailed explanation of the implementation later on. Now, the following functions show how to handle each type of vertex. We will visit the vertices in order of their $y$-coordinates.

$\mathbf{HandleStart}(v_i)$

Insert $e_i$ into $T$ and set $helper(e_i)$ to $v_i$.

$\mathbf{HandleEnd}(v_i)$

if $helper(e_{i-1})$ is a merge vertex

$\quad$ then Insert a diagonal connecting $v_i$ to $helper(e_{i-1})$.

Delete $e_{i-1}$ from $T$.

$\mathbf{HandleSplit}(v_i)$

Find the edge $e_j$ directly to the left of $v_i$ in $T$.

Insert a diagonal connecting $v_i$ to $helper(e_j)$.

$helper(e_j) \leftarrow v_i$

$helper(e_i) \leftarrow v_i$

Insert $e_i$ in $T$.

$\mathbf{HandleMerge}(v_i)$

if $helper(e_{i-1})$ is a merge vertex

$\quad$ then Insert a diagonal connecting $v_i$ to $helper(e_{i-1})$.

Delete $e_{i-1}$ from $T$.

Find the edge $e_j$ directly to the left of $v_i$ in $T$.

if $helper(e_{j})$ is a merge vertex

$\quad$ then Insert a diagonal connecting $v_i$ to $helper(e_{j})$.

$helper(e_j) \leftarrow v_i$

$\mathbf{HandleRegular}(v_i)$

if the interior of $P$ lies to the right of $v_i$

$\quad$ then if $helper(e_{i-1})$ is a merge vertex

$\quad$ $\quad$ then Insert a diagonal connecting $v_i$ to $helper(e_{i-1})$.

$\quad$ Delete $e_{i-1}$ from $T$.

$\quad$ $helper(e_i) \leftarrow v_i$

$\quad$ Insert $e_i$ in $T$.

else Find the edge $e_j$ directly to the left of $v_i$ in $T$.

$\quad$ if $helper(e_{j})$ is a merge vertex

$\quad$ $\quad$ then Insert a diagonal connecting $v_i$ to $helper(e_{j})$.

$\quad$ $helper(e_j) \leftarrow v_i$

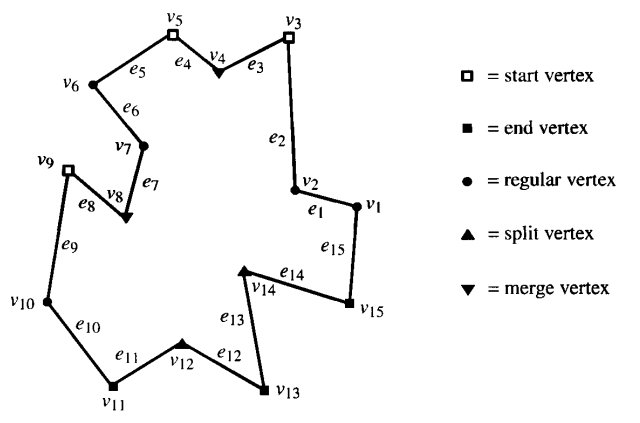

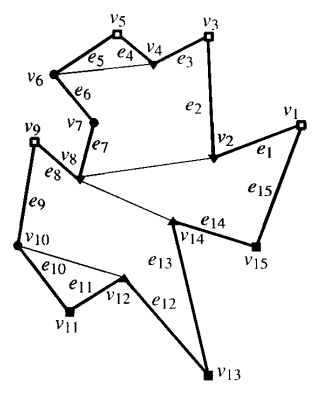

The following image shows the result of the algorithm.

Implementation Details

There is one thing I’d like to mention about implementation, and that is the data structure $T$. Obviously we would have to use some kind of binary search tree. In my case, since I used C++ for the implementation, I used the set container that is built in the standard library. Since none of the edges in the search tree intersect, we just have to compare the $x$-coordinate of the intersection points between each edge and a line parallel to the $x$-axis and passes through the current point. Therefore I simply created a custom compare function that does exactly this. Then, finding the edge is as simple as calling the lower bound function.

Proofs

Lets go over some proofs that I skipped over in the explanation.

$What \space to \space Show$: A polygon is $y$-monotone if it has no split or merge vertices.

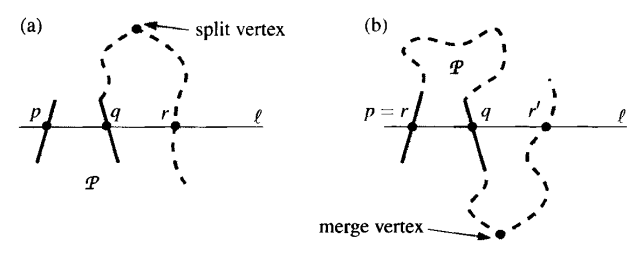

$Proof$: Suppose a polygon $P$ is not $y$-monotone. Then, there is a horizontal line $l$ that intersects $P$ in more than one connected component. Lets choose one $l$ so that the leftmost component is a segment and not a point.

Let $p$ be the left endpoint of this segment, and $q$ the right endpoint. Now, starting from $q$ we’re going to follow the boundary of $P$ so that the interior of $P$ is on the left (in other words, go up). At some point $r$, the boundary will intersect $l$ again. If $p \ne r$, then the highest vertex encountered while going from $q$ to $r$ must be a split vertex.

Otherwise, if $p = r$, we follow the boundary of $P$ starting from $q$, but this time in the opposite direction. Again, the boundary will intersect $l$ at some point $r’$. If $r’ = p$, then $l$ only intersects $P$ twice, which contradicts the fact that $l$ intersects $P$ in more than one component. Therefor $r’ \ne p$, meaning that the lowest vertex encountered while going from $q$ to $r’$ must be a merge vertex.

Therefore if $P$ is not $y$-monotone, $P$ must have a split or merge vertex, and the proof is done. $\blacksquare$

$What \space to \space Show$: The algorithm explained adds a set of non-intersecting diagonals that partitions $P$ into monotone sub-polygons.

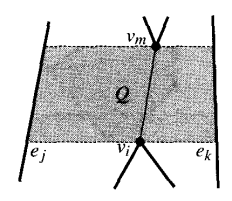

$Proof$: It is easy to see that the pieces that have been partitioned contain no split or merge vertices, therefore being monotone. Now all that remains is to prove that the diagonals are valid, meaning they don’t intersect the edges of $P$. We’re going to prove this for the segment added in $\mathbf{HandleSplit}$, as the others can be proven similarly.

Consider a segment $\overline{v_mv_i}$ that has been added. Let $e_j$ be the edge to the left of $v_i$ and $e_k$ the edge to the right. Note that $helper(e_j) = v_m$ when we reach $v_i$. First, we’ll show that $\overline{v_iv_m}$ does not intersect an edge of $P$. Consider the quadrilateral $Q$ bounded by two horizontal lines passing through $v_i$ and $v_m$, and $e_j$ and $e_k$. Since $v_m$ is the helper of $e_j$, there are no vertices inside $Q$. Suppose an edge of $P$ intersects $\overline{v_iv_m}$. Since the edge cannot have an endpoint in $Q$ and polygon edges don’t intersect each other, the edge must intersect the horizontal segment connecting $v_m$ to $e_j$, or $v_i$ to $e_j$. Both scenarios are impossible since $e_j$ lies immediately to the left of both $v_i$ and $v_m$. Therefore no edge of $P$ can intersect $\overline{v_iv_m}$.

Now consider a previously added diagonal. Since no vertices of $P$ lie inside $Q$, both endpoints of any diagonal added previously must be above $v_i$, and therefore cannot intersect with $\overline{v_iv_m}$. $\blacksquare$

Intermission - Finding Faces

The next step of the triangulation algorithm is to triangulate each of the monotone pieces we created. But before that, we must separate the pieces that we created. In other words, we must find the faces in the planar graph we created by adding edges. Thankfully, this isn’t so hard.

Basically, we sort all adjacent edges to a certain vertex by polar angle. Then we start at some vertex and traverse the edges in order until we return to the place we started. When choosing which edge to move next to, we can simply use an edge we haven’t used before. With this process, every cycle we make will be a face of the planar graph. Keep in mind that the result will also include the original polygon, so we must also exclude that later (unless the original polygon is monotone). Since the number of edges is $O(N)$, the entire process takes under $O(NlogN)$ time.

Check this link to look in detail how this works.

Part 2 - Triangulating Monotone Polygons

Explanation

Let $P$ be a $y$-monotone polygon, where the $y$-coordinate of all vertices are different. Because the polygon is monotone, it can be split into two chains on the left and right. The process of triangulating a monotone polygon is actually quite simple, since all we do is greedily add diagonals whenever we can. Lets see how this works in detail.

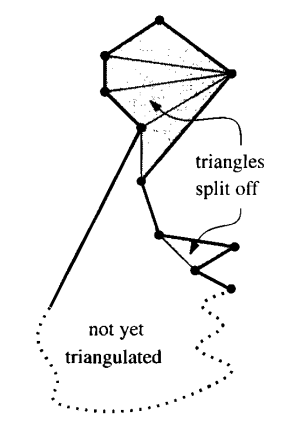

Like always, we will look at the vertices in order of decreasing $y$-coordinates. The algorithm requires a stack $S$ to maintain the vertices. Initially $S$ is empty, and later it contains the vertices of $P$ that has been encountered but still needs more diagonals. When handling a vertex, we add as many diagonals as possible from this vertex to the other vertices in the stack. The new diagonals split off triangles from $P$. In $S$, there are the vertices that have been handled but not split off. The lowest of these vertices is on the top of the stack, the second lowest is on the second in the stack, and so on. The part of $P$ that still needs to be triangulated and lies above the current vertex has a certain shape, one that looks like an upside down funnel. One boundary of this funnel is a single edge of $P$. The other boundary is a chain of vertices, where the interior angle is at least 180$^{\circ}$(we call these reflex vertices). Only the highest vertex, which is at the bottom of the stack, is convex. It is easy to see that this property remains true after we handle the next vertex.

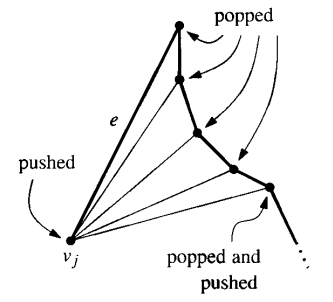

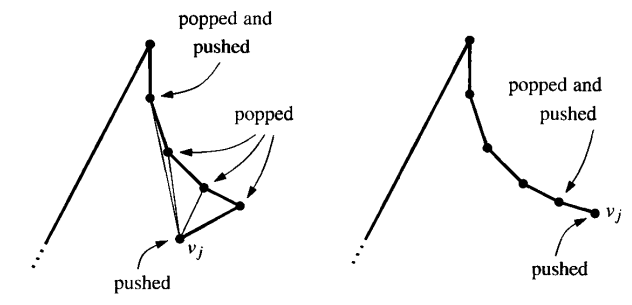

Now lets see what diagonals we should add when handling the next vertex. There are two cases: $v_j$, the vertex to be handled, lies on the same chain as the reflex vertices, or it lies on the opposite chain. If $v_j$ is on the opposite chain, it must be the lower endpoint of a single edge $e$ bounding the funnel. Thanks to the shape of the funnel, we can simply add diagonals from $v_j$ to all other vertices in the stack except the last one (the one on the bottom of $S$). This last vertex will be the upper endpoint of $e$, and therefore is already connected to $v_j$. All these vertices are popped from $S$. Now the untriangulated part of $P$ above $v_j$ is bounded by the diagonal that connects $v_j$ and the vertex that previously on the top of $S$, and an edge of $P$ that extends downwards from this vertex, and therefore the funnel shape is preserved. This vertex (the previous top) and $v_j$ are still part of the untriangulated polygon, so they are pushed back in $S$.

The next case is when $v_j$ is on the same chain as the reflex vertices. In this case, we cannot simply add diagonals to all vertices in $S$. However, the ones we can connect to $v_j$ are consecutive and on the top of the stack, and therefore we can proceed like the following. First, we pop one vertex from $S$. This vertex is already connected to $v_j$ by an edge of $P$. Next, we can pop vertices from $S$ until we encounter one that is not possible. Checking whether or not we can draw a diagonal from $v_j$ to a vertex $v_k$ on a stack can be done by looking at the vertices $v_j$, $v_k$, and the previous vertex that was popped. By checking which chain these vertices are on (left or right) and in which order they are placed (clockwise or counter-clockwise), we can easily tell if a diagonal from $v_j$ to $v_k$ can be added or not. Once we encounter a vertex which we can’t add a diagonal to, we push the last vertex that has been popped back into $S$. This will either be the last vertex which a diagonal has been added to, or the neighbor of $v_j$ on the boundary of $P$. Then we push $v_j$ into $S$. Here, the shape of the funnel is still present.

Now, we can construct a full algorithm for the process.

The Algorithm

The algorithm is kind of similar to the convex hull algorithm.

$\mathbf{TriangulateMonotone}(P)$

Input: A $y$-monotone polygon $P$

Output: A triangulation of $P$

Sort the vertices of $P$ in order of decreasing $y$-coordinate. Let $u_1, u_2, \cdots, u_n$ denote the sorted sequence.

Initialization: An empty stack $S$, and push $u_1$, $u_2$ into it.

for $j \leftarrow$ $3$ to $n-1$

$\quad$ if $u_j$ and the vertex on top o $S$ are on different chains

$\quad$ $\quad$ then Pop all vertices from $S$

$\quad$ $\quad$ $\quad$ Insert a diagonal from $u_j$ to each popped vertex except the last one.

$\quad$ $\quad$ $\quad$ Push $u_{j-1}$ and $u_j$ into $S$.

$\quad$ else Pop one vertex from $S$.

$\quad$ $\quad$ Pop the other vertices from $S$ as long as the diagonal from $u_j$ to them are inside $P$.

$\quad$ $\quad$ Add the diagonals that are inside $P$.

$\quad$ $\quad$ Push the last vertex that has been popped back into $S$.

$\quad$ $\quad$ Push $u_j$ into $S$.

Add diagonals from $u_n$ to all vertices in $S$ except for the first and last one.

And with that, combining this with the previous algorithms, we are done.

Implementation Details

There isn’t much to mention here, as the algorithm itself is quite simple. The only thing that I think is worth mentioning is figuring out which chain each vertex is on, and how to tell f we can add a diagonal in the second case. As for finding the chain, we can find the vertex with the highest $y$-coordinate, and traverse the boundary of the polygon. We put the vertices we meet on the same chain, until we meet the lowest vertex, which is the one that has a lower $y$-coordinate than its two neighbors. Then we can put the rest of the vertices on a different chain.

To check whether or not we can add a diagonal, lets call the next vertex $v_j$, the vertex we want to add a diagonal to $v_k$, and the vertex that has been popped most recently $v_i$. If these three vertices are on the right chain, then we can add a diagonal if $v_j \rightarrow v_i \rightarrow v_k$ is in counter clockwise order, and if they are on the left chain, then we can add a diagonal if they are in clockwise order. This is easy to see, and also easy to implement.

Full Implementation

Now that we have gone over all the necessary algorithms to triangulate a polygon in $O(NlogN)$, all we have to do is implement every step, and put them together. This could be a little intimidating, but I found it to be pretty straight forward, without any major difficulties. By the very least, it was way easier than implementing the algorithm finding the convex hull of circles.

I implemented the entire thing in C++, and ended up with 307 lines of code, which you can find here on my GitHub. I didn’t thoroughly test it though, so there could be some errors. Also, while I did try to write the code as clean as possible, readable code isn’t really my strong suit, so sorry for that.

One final note: through out the explanation we always assumed that all vertices had different $y$-coordinates, but this might not be the case sometimes. However, this is easy to handle, since we can just rotate the polygon a very small amount (1$^{\circ}$ should be enough), and then all vertices will have different $y$-coordinates.

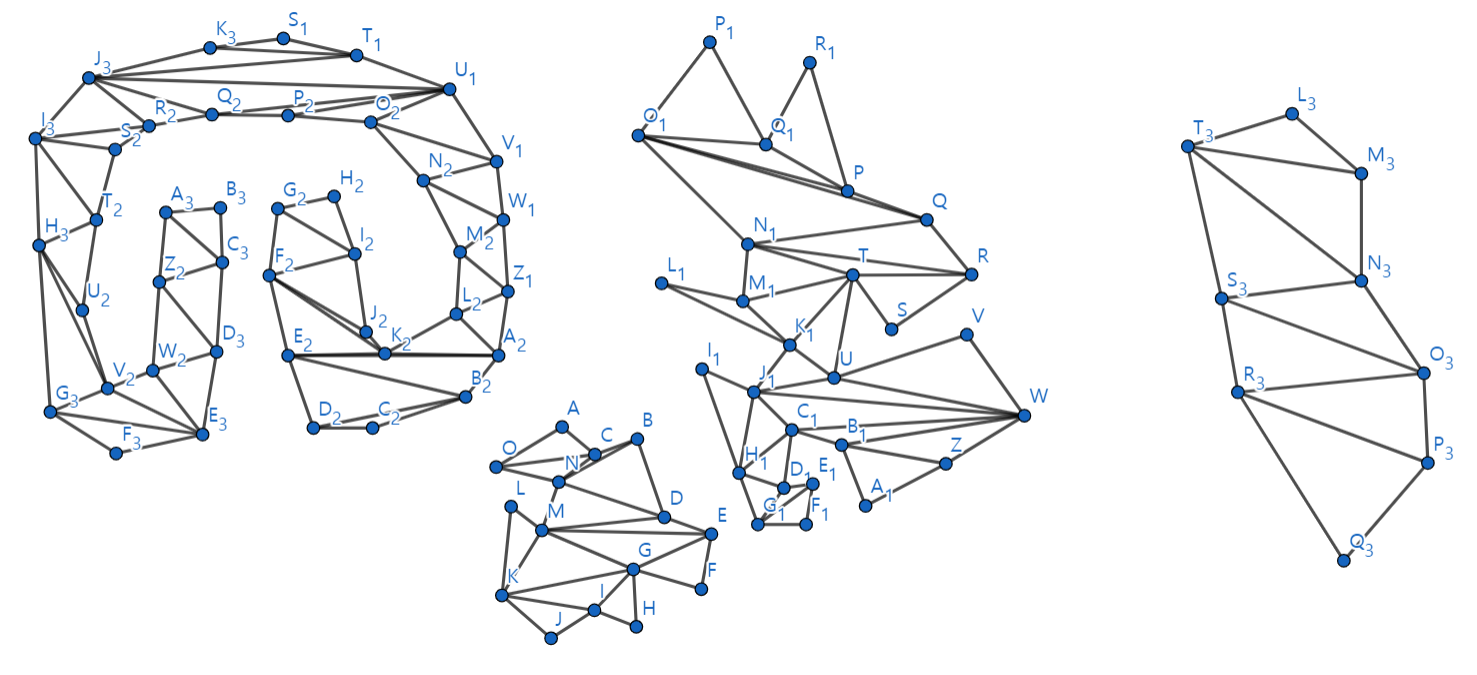

The following image shows some results I got from inputting different polygons I hand-made.

Conclusion

So that was how to triangulate a polygon in $O(NlogN)$. Note that we did not use the fact that the polygon was simple in any part of the algorithm, meaning that the algorithm can be used on any polygon, even one with holes, as long is doesn’t self-intersect. However, my code can only handle simple polygons.

Personally, I find this algorithm to be quite simple and on the easier side to implement. Once I understood each part, implementing them wasn’t so difficult, and I didn’t run into any major problems, which is very rare when implementing anything related to geometry. So, that was a relief.

In this post I only went over the triangulation algorithm. In the future I would like to go over some uses of the triangulation algorithm like the ones I mentioned at the start of this post (art gallery problem, shortest path in simple polygon). Hopefully I can work on it soon.

And with that, thank you for reading.

Reference

Marc van Kreveld, Mark Overmars, and Mark de Berg, “Computational Geometry: Algorithms and Applications”