Recently, I wrote a short report about graphs and matrices for an assignment in my linear algebra class. So I thought I would write it here on my blog as well. I thought just uploading the pdf, but its written in Korean so here we go.

Graphs and Adjacency Matrix

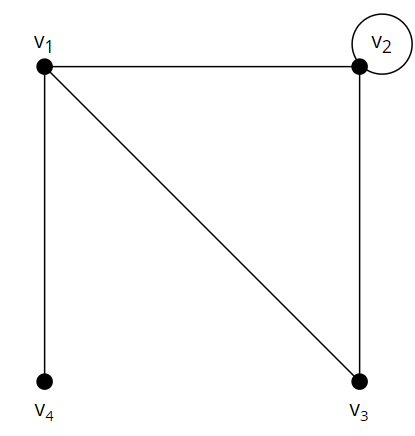

A graph consists of multiple points called a vertex and edges that connect two vertices. When two vertices are connected, we call these two adjacent. It is not necessary for an edge to connect two different vertices. Also, the same two vertices can be connected by more than one edge, but for the sake of simplicity, let’s assume this is not the case.

A graph can be represented as a matrix, and operations on this matrix can tell us a few things about the graph. A graph can be represented as a matrix in the following way:

Let $G$ be a graph with $n$ vertices. Then the adjacency matrix of $G$ is a $n \times n$ matrix $A$ where

\[a_{ij} = \begin{cases} 1 &\text{$i$ and $j$ are adjacent}\\ 0 &\text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]is true.

The following matrix is the adjacency matrix $A$ of the graph in the image above.

\[A = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 1 & 1\\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 0\\ 1 & 1 & 0 & 0\\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\]The adjacency matrix of a graph has an interesting property. Consider the following matrix $A^2$.

\[A^2 = \begin{bmatrix} 3 & 2 & 1 & 0\\ 2 & 3 & 2 & 1\\ 1 & 2 & 2 & 1\\ 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\]If you look at the graph closely, you can see that the $(i,j)$ component of $A^2$ is equal to the number of paths in the graph of length 2, that start from $v_i$ and end at $v_j$. If you think about this, the $(i,j)$ component of $A^2$ is calculated as the sum of $a_{ik}a_{kj}$ for all $1 \leq k \leq n$. The only way for this to be non-zero is for $a_{ik}$ and $a_{kj}$ to be both non-zero, or one. This means that there is an edge that connects $v_i$ and $v_k$, and an edge that connects $v_k$ and $v_j$. In other words, there is a path from $v_i$ to $v_j$ whose length is 2. Obviously, the sum would give the number of such paths. This can be expanded to the following statement.

Let $A$ be the adjacency matrix of $G$. Then the $(i,j)$ component of $A^n$ is equal to the number of paths from $v_i$ to $v_j$ that has a length of $n$.

$Proof$: The statement can be solved using induction. When $n = 1$, $a_{ij}$ should give the number of paths from $v_i$ to $v_j$. This is the definition of an adjacency matrix, and thus is true. Next, lets assume that $A^k_{ij}$ is equal to the number of paths from $v_i$ to $v_j$ that has a length of $k$. Then, $A_{ij}^{k+1} = \Sigma_{l=1}^{m} A^k_{il} A_{lj}$. For some vertex $v_l$, $A^k_{il}$ is equal to the number of paths from $v_i$ to $v_l$ with length $k$, and $A_{lj}$ is equal to the number of paths from $v_l$ to $v_j$ with length 1(this is either 1 or 0). There for the product of these two will be the number of paths with length $k+1$ from $v_i$ to $v_j$ that passes $v_l$. Adding this for all $v_l$ will give us the number of paths from $v_i$ to $v_j$ that has a length f $k+1$, proving the inductive step. $\blacksquare$

Bipartite Graphs

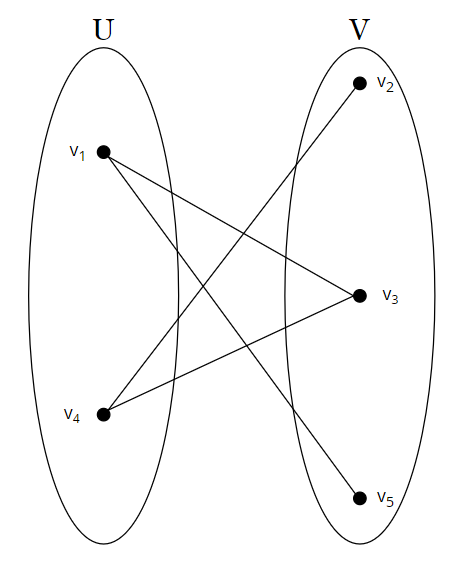

If vertices of a graph can be separated into two groups $U$ and $V$ so that for every edge a vertex from one end is in $U$ and the other is in $V$, we call this graph bipartite.

The adjacency matrix of a bipartite has a property that it is possible to label the vertices so that the adjacency matrix has the following shape.

\[A = \begin{bmatrix} O & B\\ B^T & O\\ \end{bmatrix}\]Also, if it is possible to label the vertices so that the adjacency matrix looks like the above, the graph is bipartite. Lets prove this.

$Proof$: ($\rightarrow$) Lets say the adjacency matrix of a graph $G$ can be represented as the above. Lets say the two zero blocks have $p$ and $q = n-p$ rows. Then, since the upper left $p \times p$ block consist of only zeros, any edge connecting $v_1, v_2, \cdots, v_p$ will have its other end connected at $v_{p+1}, v_{p+2}, \cdots, v_n$. Similarly, the lower right $q \times q$ block also consists of only zeros, and therefore any edge connecting $v_{p+1}, v_{p+2}, \cdots, v_n$ will have its other edge connected at $v_1, v_2, \cdots, v_p$. Therefore $G$ is a bipartite graph where $U = {v_1, v_2, \cdots, v_p}$ and $V = {v_{p+1}, v_{p+2}, \cdots, v_n}$.

($\leftarrow$) Lets say $G$ is a bipartite graph. Also, lets say we labeled the vertices so that $U = {v_1, v_2, \cdots, v_p}$ and $V = {v_{p+1}, v_{p+2}, \cdots, v_n}$. Now lets think about the adjacency matrix $A$. If $i, j \leq p$, then $v_i$ and $v_j$ are both in $U$, and therefore $a_{ij} = 0$. Similarly, if $i,j > p$, then $v_i$ and $v_j$ are both in $V$, and therefore $a_{ij} = 0$. In other words, the upper left $p \times p$ block consists of all zeros, and the lower right $q \times q$ block also consists of all zeros. Also, since $G$ is undirected, $a_{ij} = a_{ji}$, and therefore the remaining two blocks are transposes of each other. $\blacksquare$

Another thing about bipartite graphs is that they have no cycles of odd length. This is pretty straightforward if you think about it. However, it is possible to prove this using the adjacency matrix we just proved above.

$Proof$: Lets say that $G$ is a bipartite graph, and the adjacency matrix $A$ has the form of the above. We will prove the statement by showing that an odd power of $A$ consists of an upper left $p \times p$ zero block and a lower right $q \times q$ zero block. First, $A^1 = A$ and therefore works. Then if we calculate $A^2$ we get

\[A^2 = \begin{bmatrix} OO+BB^T & OB+BO\\ B^TO+OB^T & B^TB+OO\\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} BB^T & O\\ O & B^TB\\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} D_1 & O\\ O & D_2\\ \end{bmatrix}\]Lets assume that $A^{2k-1}$ has the shape we want. Then we can calculate $A^{2k+1}$ like the following.

\[A^{2k+1} = A^{2k-1}A^2 = \begin{bmatrix} O & C_1\\ C_2 & O\\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} D_1 & O\\ O & D_2\\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} O & C_1D_2\\ C_2D_1 & O\\ \end{bmatrix}\]Therefore $A^{2k+1}$ also has the shape we want, proving that an odd power of $A$ will consist of an upper left $p \times p$ zero block and a lower right $q \times q$ zero block. The components of $A^{2k+1}$ gives us the number of paths with an odd length. Because of its shape, we know that the diagonal components are all zero, meaning that there is no path of odd length that starts and ends at the same vertex. In other words, there is no cycle that has an odd length. $\blacksquare$

Directed Graphs

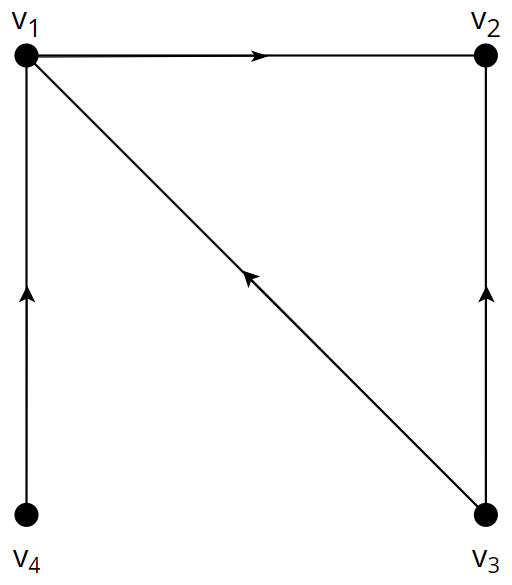

If the edges of a graph $G$ have directions, we call this graph a directed graph or digraph. If the direction of an edge is $v_i \rightarrow v_j$, then it is not possible to go from $v_j$ to $v_i$. Obviously, the adjacency matrix of a directed graph may not be symmetric. As well as undirected graphs, the value $[A^n]_{ij}$ also represents the number of paths with length $n$ from $v_i$ to $v_j$ in a directed graph.

If a directed graph does not contain any cycles, we call this graph a DAG(directed acyclic graph). A fun thing about DAGs(while there are many), is the fact that it is possible to know the existence of a hamiltonian cycle by looking at its adjacency matrix. Lets think about the matrix $B = I - A$. $B$ has the opposite meaning of $A$, where if $b_{ij} = 1$ there is no edge going from $v_i$ to $v_j$, and else there is. Lets call this the anti-adjacency matrix. Then surprisingly, if $\text{det}B = 1$, then there is a hamiltonian path, and if $\text{det}B = 0$, there is no hamiltonian path. To prove this we must prove the following lemma first.

$\text{Lemma}$: If $A$ is an $n \times n$ matrix where $a_{ij} = 1$ if $i \geq j$, then if $a_{12} = a_{23} = \cdots = a_{n-1n} = 0$ $\text{det}A = 1$, else $\text{det}A = 0$

$Proof$: If $a_{12} = 1$ then the first two rows of $A$ become equal, and therefore $\text{det}A = 0$. Lets say $a_{12} = 0$. If we subtract the second row from the first row, then all the elements in the first row of $A$ except $(1,1)$ become 0. Now, if we expand on the first row, we get a $n-1 \times n-1$ matrix where the $(i,j)$ component is 1 if $i \geq j$. By induction, if any one of $a_{12}, a_{23}, \cdots, a_{n-1n}$ equals 1, then $\text{det}A = 0$. Otherwise, $\text{det}A = 1$. $\blacksquare$

Now, lets prove the following.

If $G$ is a $DAG$ with $n$ vertices, and $B$ is the anti-adjacency matrix of $G$, then if $G$ has a hamiltonian path, $\text{det}B = 1$, and $\text{det}B = 0$ otherwise.

$Proof$: Lets $G$ has a hamiltonian path. Without loss of generality, lets say this path is $1 \rightarrow 2 \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow n$. Since $G$ has no cycles, if $i > j$ then there is no edge going from $i$ to $j$. Therefore if $i \geq j$ then $b_{ij} = 1$. Also, since $b_{12} = b_{23} = \cdots = b_{n-1n} = 0$, by the lemma $\text{det}B = 1$.

Lets say that $G$ does not have a hamiltonian path. Since $G$ has no cycles, there exists a source vertex(a vertex that has no edges going into it). Without loss of generality, lets call this vertex 1. Similarly in $G/{1}$(The graph $G$ without vertex 1), there will be a source vertex, and we will call this vertex 2. Like this, we will set the $i^{th}$ vertex as the source vertex in $G/{1, 2, \cdots, i-1}$. This way, there will be no edge that connects $i$ and $j$ when $i > j$, and therefore if $i \geq j$ then $b_{ij} = 1$. Also, if there exists a vertex from $i$ to $i+1$ for all $1 \leq i \leq n-1$, then this means there exists a hamiltonian path $1 \rightarrow 2 \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow n$. Therefore there has to be at least one case where there is no edge from $i$ to $i+1$. In other words, there is at least one $b_{12}, b_{23}, \cdots, b_{n-1n}$ that is one. Therefore by the lemma, $\text{det}B = 0$. $\blacksquare$

Lets look at the following example.

The anti-adjacency matrix of the above graph will look like the following.

\[B = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1\\ 1 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 1\\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0\\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 0\\ 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\]In the matrix, the $(i,j)$ component is equal to 1 when $i \geq j$, and $b_{12} = b_{23} = b_{34} = b_{45} = 0$. Therefore by the lemma we proved $\text{det}B = 1$, and if you actually find the determinant, it equals 1 as well. Therefore the graph has a hamiltonian path, which is $v_1 \rightarrow v_2 \rightarrow v_3 \rightarrow v_4 \rightarrow v_5$.

Conclusion

In this post I wrote some simple relations between graphs and matrices. Obviously there’s a lot more, such as the laplacian matrix, Kirchhoff’s theorem, and so on. But those are for another time.

Reference

R. B. Bapat, Graphs and Matrices: link