Its been a while since I posted something. No excuses, I was just lazy. Now, on with the post.

Some Backstory

Some time ago me and a few of my friends were preparing a problem for a test for my school club. One of my favorite parts of problem solving is computational geometry. So I decided to make a geometry problem.

As for exactly what kind of problem, I wasn’t so sure. I surfed the internet to find some inspiration, when I came across a problem called Security Zone, from GCPC 2011.

To summarize the problem, you are given a set of circles, and must find the length of the convex hull of those circles. One thing I noticed about this problem was that the constraints for the number of circles was very small, with a maximum of 25 circles per test case, meaning that almost any kind of time complexity would work. So natuarly I thought, why not ramp up that number? Like 50000?

And so I searched to see if there were any algorithms or problems related to this. Another problem I found was a problem called Craters, from the 2017 East Central Regional Contest.

This problem is almost identical to Security Zone. One of the major differences, however, was that the maximum number of circles is 200. 200 is larger than 25, but still, most time complexitys would still work. I wanted more.

A bit after I saw Security Zone, I came across a paper by D. Rappaport called “A convex hull algorithm for discs, and applications”, and inside, was an $O(NlogN)$ algorithm for finding the convex hull of circles.

I had no idea about the hell I was gonna go through implementing and creating a problem out of that.

Introduction

A convex hull of some shapes is the smallest convex set that contains the shapes. Finding the convex hull of a set of points is a famous problem in computational geometry, and is also probably one of the most well-known.

While there are multiple algorithms for finding the convex hull of points, there seems to be a lack of algorithms regarding the convex hull of other shapes. Or mabye I just didn’t search hard enough, which is likely. Related problem solving, there are a lot of problems that use the convex hull of points, but not for other shapes.

As I have said in the backstory, I recaintly found an article about an $O(NlogN)$ algorithm for finding the convex hull of circles, implemented it, and made a problem for it. It was hard.

In this post I’m going to explain the algorithm written in the paper, as well as some tips for implementation that I thought would be useful.

I’m writing this post in hopes that it could surface this and similar algorithms(which is unlikely), and mabye get you into computational geometry(which is even more unlikely).

Without further ado, lets start.

Notations

Lets begin by defining a few notations. Some of these notations aren’t used that much, but I’ll still write them down.

- $Hull(S)$: The convex hull of $S$

- $\partial(R)$: The boundary of $R$

- $H(L)$: When $L$ is a directed line, $H(L)$ denotes the right halfplane of $L$

- $support \space line$: If $S \in H(L)$ and no subset of $H(L)$ contains $S$, we call $L$ a $support \space line$ of $S$

- $L(A,B)$: The common support line of $A$ and $B$, directed from $A$ to $B$(if one exists)

- $t(A,B)$: A subset of $L(A,B)$, where one end lies on $\partial(A)$ and the other lies on $\partial(B)$

- $edge$: When $a,b \in S$ and $L(a,b)$ is a support line of $Hull(S)$, we call $t(a,b)$ an $edge$ of $Hull(S)$

- $CH(S)$: An array of $s$ where $s \in Hull(S)$. The elements are sorted in clockwise order. Also, the first and last element are kept the same.

- $bridge$: If $p \in P$, $q \in Q$, and $L(p,q)$ supports $CH(P \cup Q)$, we call $t(p,q)$ a $bridge$ of $CH(P)$ and $CH(Q)$

The following are a few functions we will use within the algorithm.

- $\alpha(L_1,L_2)$: When $L_1,L_2$ are directed lines, returns the angle swept clockwise from $L_1$ to $L_2$

- $succ(s)$: When $s \in CH(P)$, returns the successor of $s$ in $CH(P)$. If $s$ is the last element, returns the first element of $CH(P)$

- $dom(L_p,L_q$): When $L_p$ and $L_q$ are parallel support lines of $P$ ans $Q$, returns true if $H(L_q) \in H(L_p)$, and false if otherwise

- $Add(\vartheta,\psi)$: If $\psi$ is the last element of $\vartheta$, return $\vartheta$, otherwise add $\psi$ to the end of $\vartheta$ and return $\vartheta$

Size of the Convex Hull

For the algorithm to run in $O(NlogN)$ time, the size of the convex hull must be $O(N)$. This is true for points where each point can only be contained at most once in the convex hull. In the case of circles, a circle can be contained multiple times in the convex hull, at most $N-1$ times. Therefore it might not be obvious that the size of the convex hull is $O(N)$.

However, it can be shown that the size of the convex hull of $N$ circles is at most $2N-1$. Heres the proof:

$What \space to \space Show$: $\lvert CH(S) \rvert \leq 2N-1$.

$Proof$: Let $u,v$ be 2 circles in $CH(S)$, and $S_0$ ~ $S_4$ subsets of $CH(S)$ so that $CH(S)$ can be written as $S_0,u,S_1,v,S_2,u,S_3,v,S_4$. First, suppose that the size of $S_1$ and $S_3$ are 0. Then, $t(u,v)$ must appear as an edge on $CH(S)$ twice, which makes no sense. Now, suppose that the size of $S_1$ is not 0. That means that $L(u,v)$ must intersect with $Hull(S)$ at some point $\psi$. However, the second appearance means that there is another intersection with $L(u,v)$ and $Hull(S)$ that isn’t $\psi$, which is a contradiction. In other words, $u,\cdots,v,\cdots,u,\cdots,v$ is an impossible sequence in $CH(S)$.

Such a sequence where $u,\cdots,v,\cdots,u,\cdots,v$ doesn’t appear is known as a Davenport-Schinzel sequence of order 2. It is proven that the maximum length of such a sequence is $2N-1$. Therefore the size of $CH(S)$ cannot be larger than $2N-1$. $\quad\blacksquare$

An example of a case where the size of $CH(S)$ is equal to $2N-1$ is when there is one large circle and $N-1$ small circles adjacent to it. In such a case, $CH(S)$ would look something like this: $(1,n,2,n,3,n,\cdots,n-1,n,1)$.

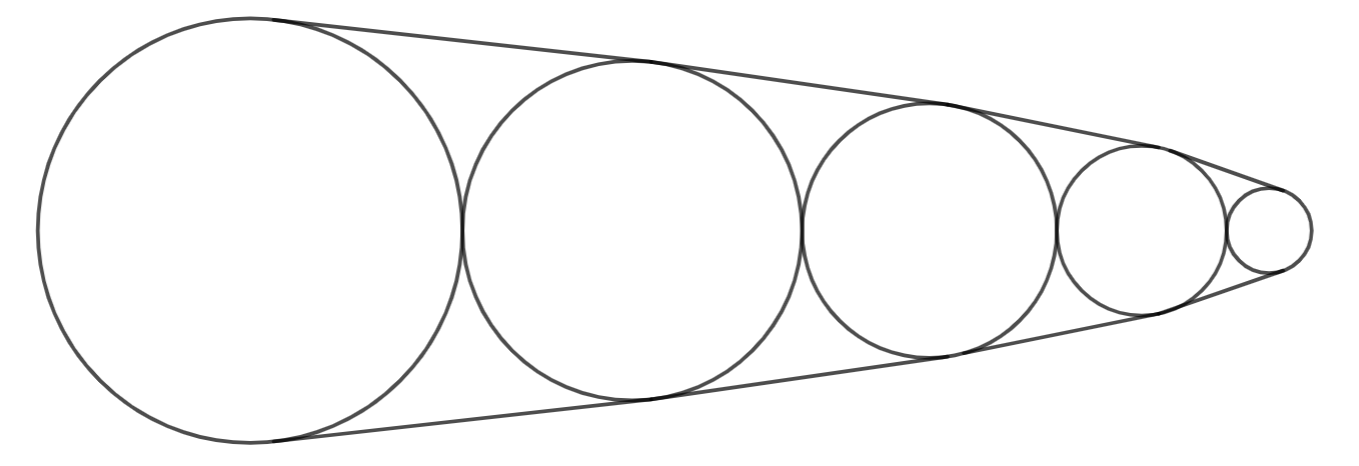

Another example would be when N circles with radius 1 to $N$ are put so that their centers lie on a striaght line in decreasing order, while staying adjacent to the circles next to it. In such a case, $CH(S)$ would look something like this: $(1,2,3,\cdots,n-1,n,n-1,\cdots,3,2,1)$

The Algorithm

Now, lets actually get into the algorithm.

The Idea

The general idea of the algorithm is to use divide and conquer the hull. When we have a set of circles $S$, we split it into two sets $P$ and $Q$ whose size differ by at most 1. We then recursively find $CH(P)$ and $CH(Q)$. After that, we use a process called $merge$ to merge the two convex hull, finding $CH(S) = CH(P \cup Q)$.

The way we merge two convex hulls is by having two parallel sweep line that each support $CH(P)$ and $CH(Q)$ rotate around each hull. At each iteration, we check whether the current arc is contained in $CH(P \cup Q)$, and add it to the hull.

The Algorithm

$\mathbf{Hull}$

1. Split $S$ into two different sets $P$ and $Q$ whose size differ by at most 1.

2. Recursively find $CH(P)$ and $CH(Q)$.

3. Use the process/algorithm $merge$ to merge the two hulls, resulting in $CH(S) = CH(P \cup Q)$.

$\mathbf{Merge}$

Input: $CH(P)$ and $CH(Q)$

Output: $CH(S) = CH(P \cup Q)$

Initialization:

Let $L_p$ and $L_q$ denote support lines of $P$ and $Q$, while being tangent to $p \in P$ and $q \in Q$ such that both are parallel to a line $L^*$. Set $CH(S)$ empty.

We now use a process called $Advance$ to advance to the next arc in either $CH(P)$ or $CH(Q)$.

repeat

$\quad$ if $dom(L_p,L_q)$ then $Add(CH(S),p)$; $Advance(L^*,p,q)$;

$\quad$ else if $dom(L_q,L_p)$ then $Add(CH(S),q)$; $Advance(L^*,q,p)$;

$\quad$ $L_p \leftarrow$ Line parallel to $L^*$ and tangent to $P$ at $p$;

$\quad$ $L_q \leftarrow$ Line parallel to $L^*$ and tangent to $Q$ at $q$;

until Every edge in $CH(P)$ and $CH(Q)$ have been visited

$\mathbf{Advance(L^*,x,y)}$

Here, we test whether $t(x,y)$ and $t(y,x)$ are bridges, then advance on the minimum angle.

Also note that if $L(x,y)$ does not exist, $\alpha(L^*,L(x,y))$ is undefined.

$a_1 \leftarrow \alpha(L^*,L(x,y)); \quad a_2 \leftarrow \alpha(L^*,L(x,succ(x)));$

$a_3 \leftarrow \alpha(L^*,L(y,succ(y))); \quad a_4 \leftarrow \alpha(L^*,L(y,x));$

if $a_1 = min(a_1,a_2,a_3)$ then $Add(CH(S),y); \quad$ // $t(x,y)$ is a bridge

$\quad$ if $a_4 = min(a_2,a_3,a_4)$ then $Add(CH(S),x); \quad$ // $t(y,x)$ is a bridge too

if $a_2 < a_3$ then $L^* \leftarrow L(x,succ(x)); \quad x \leftarrow succ(x);$

else $L^* \leftarrow L(y,succ(y)); \quad y \leftarrow succ(y);$

Proof of Correctness

Now that we know the algorithm, lets prove why the algorithm above works. Lets start by proving the following:

$What \space to \space Show$: At every iteration of $Merge$, $L_p$ and $L_q$ are parallel, while each support $P$ and $Q$.

$Proof$: We first initialize $L_p$ and $L_q$ to satisfy the condition above. Lets assume that the condition is satisfied at an arbitrary iteration. Then, lets show that the condition is satisfied on the next iteration as well.

It is obvious that $L_p$ and $L_q$ are parallel. Lets think about the consecutive circles of $p$ on $CH(P)$(or $CH(Q)$, it doesn’t matter). We can know that if a line lies between $L(pred(p),p)$ and $L(p,succ(p))$, it can become a support line of $P$.

In the process $Advance$, one of $L_p$ and $L_q$ becomes a common support line of two consecutive circles. Lets say that the line that changes is $L_q$. In other words, $L_q$ becomes $L(q,succ(q))$. Since the line changes to the one that has the smaller angle, the angle of $L(q,succ(q))$ is smaller than the angle of $L(p,succ(p))$. Therefore the angle of $L_p$(after advanced) is smaller than $L(p,succ(p))$, which means it still supports $P$. In conclusion, the condition stated above is maintained at every iteration. $\quad \blacksquare$

Next, we prove that the process $Advance$ correctly finds whether $t(p,q)$ and $t(q,p)$ are bridges:

$What \space to \space Show$: Without loss of generality, when $dom(L_p,L_q)$ is true, $t(p,q)$ is a bridge only when $a_1 = min(a_1,a_2,a_3)$, and $t(q,p)$ is a bridge only when $t(p,q)$ is a bridge and $a_4 = min(a_2,a_3,a_4)$.

$Proof$: Lets say that $a_1$ is not the minimum. This means that there is one or two of $L(p,succ(p))$ and $L(q,succ(q))$ that have a smaller angle than $L(p,q)$ relative to $L^*$. This means that there is a point on $CH(P)$ or $CH(Q)$ that lies on the left of $L(p,q)$, and therefore $t(p,q)$ is not a bridge. In conclusion, $t(p,q)$ can only become a bridge when $a_1$ is the minimum. It can be proven for $t(q,p)$ using the same approach. $\quad \blacksquare$

Finally, we prove that $Merge$ correctly merges the two convex hulls:

$What \space to \space Show$: $Merge$ correctly computes $CH(S) = CH(P \cup Q)$.

$Proof$: Every edge in $CH(S)$ is either an edge on $CH(P)$ or $CH(Q)$, or a bridge connecting the two. Within $Merge$, we check for every edge on $CH(P)$ and $CH(Q)$, therefore checking every edge that can be on $CH(S)$ as well. As for bridges, within $Merge$, we check for every pair of circles $p \in P$ and $q \in Q$ that have parallel support lines. For each pair, there can be two support lines $t(p,q)$ and $t(q,p)$, which we have already proven are correctly found in $Advance$. Therefore, $Merge$ correctly computes $CH(S) = CH(P \cup Q)$. $\quad \blacksquare$

Time Complexity

The complexity of this algorithm is characterized by the reccurence relation $T(N) = 2T(N/2) + Cost(Merge)$. Since $Merge$ is an $O(N)$ algorithm, the time complexity of the full algorithm is $O(NlogN)$.

That pretty much concludes the explanation on the algorithm that written in the paper. The paper doesn’t stop here and explains about problems that can be solved using this algorithm. You can read about it if your curious. For this post, I’m only going to explain this one algorithm.

Implementation

Now lets move on to the details of actually implementing the algorithm.

Overview

Once you’ve fully understood the algorithm explained above, it might not seem that complicated, and you’re right. In fact, half of the implementation comes from calculating support lines and stuff, which is mostly math. Of course, given the nature of computational geometry, even the most subtle mistakes can completely mess you up. Especially in this problem, there are so many ways to mess up, which is mostly why it was hard to implement it.

In this section, I’m going to explain details regarding the implementation of the algorithm, including tips that I think might be helpful to anyone trying to implement this.

Pre-Defined Structures and Notations

Throughout the explanation, I will be using two structures. The first one is a circle struct, which contains the center coordinates, radius, and index of the circle. The second one is a structure representing a support line. There are multiple ways one can implement a support line, but I’m going to make it so that a support line structure contains the circle it supports, and its angle. Here, the angle is defined as the angle swept clockwise from a vector $(1,0)$ to the line.

Below are a few notations I might use while explaining:

- $r_p$: The radius of circle p.

- $x_p, y_p$: the $x$ and $y$ coordinate of the center of circle p.

- $A_x, A_y$: When $A$ is a point, the $x$ and $y$ coordinates of $A$.

Lastly, note that all angles are in radians if not specified to be degrees.

$dom(L_p,L_q)$ and $L(p,q)$

Lets start by implementing the two functions $dom(L_p,L_q)$ and $L(p,q)$. These two functions require more math than actual programming. Lets start with $dom(L_p,L_q)$.

$dom$ Implementaion

For $dom(L_p,L_q)$, we first check whether the two lines given in the input are parallel. We can do this by simply checking if the angles are the same. If not, return false. Now that we know that the two lines are parallel, we need to check if $L_q$ is on the right of $L_q$. How do we know if this is true? Take a look at the image below:

The image shows an example where $dom(L_p,L_q)$ is true. $Y$ and $Z$ each indicate the tangent point of $L_p$ and $p$, and $L_q$ and $q$. $X$ is a point on $L_p$ that is further in the direction of $L_p$ than $Y$.

One thing we can notice is that $X \rightarrow Y \rightarrow Z$ turns in counter clock-wise order. We can use this property to check whether $L_q$ is on the right side of $L_p$. In order to do this, lets start by finding the coordinates of $Y$ and $Z$.

Lets call the angle of $L_p$ and $L_q$ $\theta$. We can use this angle to find the coordinates of $Y$ and $Z$:

\[Y = (x_p + r_p\sin\theta, y_p + r_p\cos\theta), \space Z = (x_q + r_q\sin\theta, y_q + r_q\cos\theta)\]The exact coordinate of $X$ isn’t important. It just hast to be further in the direction of $L_p$. The way I calculated the coordinate of $X$ is by moving $Y$ by $\cos\theta$ in the $x$ axis, and $-\sin\theta$ in the $y$ axis. In other words:

\[X = (Y_x + \cos\theta, Y_y - \sin\theta)\]I used this method because it reuses $\sin\theta$ and $\cos\theta$ rather than calculating a new value using a trig function, which can be pretty expensive in programming.

Now that we have the coordinates of the three points, we can use a CCW function(or cross product, if you prefer) to check whether they are in counter-clockwise order. And with that, the $dom$ function is finished. Lets move on to $L(p,q)$.

$L(p,q)$ Implementation

The function $L(p,q)$ must return the angle of the common support line of the circles $p$ and $q$. Before we do, however, there are two cases we must consider.

The first case is when the two circles are the same. In this case, any angle can become the angle of the common support line. I just returned an arbitrary large number in this case to indicate the fact that the inputed circles are the same.

The second case is when the two circles don’t have a common support line. This can only happen when one circle is contained within another circle. Thankfully, this is easy to detect. We just check if the distance between the two centers is smaller than the difference between the two radii. If this happens to be true, I just returned an arbitrary small number, opposite to the first case, to indicate that it is the second case.

Now that the two corner cases have been taken care of, lets actually find the angle. This can be done by using some simple trigonometry. Take a look at the image below:

In the image, $C$ and $D$ represents the tangent points of $p$ and $q$. Our goal is to find $\angle OBH$, the one where the angle is larger than 180 degrees.

By looking at the image, it is easy to tell that the desired angle is equal to $\frac{\pi}{2} - \alpha + \beta$. So all we have to do is find $\alpha$ and $\beta$, which is really simple.

To find $\alpha$, we use cosines. More specifically, we can tell from the image that

\[\cos\alpha = \frac{\overline{AH}}{\overline{AB}} = \frac{|r_p - r_q|}{\overline{AB}}\]and therefore

\[\alpha = \arccos{\frac{|r_p - r_q|}{\overline{AB}}}\]Next, to find $\beta$ we use tangents. Using the inverse tangent function will give us the angle between $\overline{AB}$ and the $x$ axis swept counter-clockwise. Since $\beta$ is the angle swept clockwise, we simply need to multiply the result of the inverse tangent with -1. In other words:

\[\beta = -\arctan{\frac{B_y - A_y}{B_x - A_x}}\]The result of $\arctan$ can differ based on the sign of the numerator and the denominator. I avoided this issue by using a C++ function called $atan2$.

As the final result, we just have to return $\frac{\pi}{2} - \alpha + \beta$ and were done implementing $L(p,q)$. Some of you might be curious as to whether this works in all different arrangements of circles, and the short answer is yes. As for why it works, I’ll leave that for you to figure out.

Minor Details and Functions

With $dom$ and $L(p,q)$ out of the way, the majority of the hard work is done, and only the simple steps remain. Lets start with the remaining two functions, $\alpha$ and $Add$.

For $\alpha(L_p,L_q)$, all we have to do is subtract the angle of $L_q$ with $L_p$ and return the value. $Add(\vartheta,\psi)$ is pretty self explanatory. Just check the last element of $\vartheta$, add $\psi$ depending on what it is, and return $\vartheta$.

Next, there are a few details you might want to consider when implementing. The first, if your using C++ like me, then since we’re dealing with real numbers, or doubles, we have to becareful when comparing numbers, as C++ doubles aren’t super precise. The next is that it is a good idea to make sure that every angle calculated is modified to fit in the range of $[0,2\pi)$(or $[-\pi,\pi)$ if you prefer) to stop the values from spiraling out of control. Doing so also makes it easier to think about the angles.

Another detail is that, again, if your using C++ to implement it like me, becareful when using vectors. Functions like clear() in vectors run in $O(N)$ time, which can cause your code to become very slow. Also, when making a function, it is a good idea not to pass in vectors as a parameter, as this also makes your code very slow(trust me, I learned this the hard way). You can avoid this by making the vectors as a global variable, or using the reference as a parameter(by adding \&).

Last but not least, there could be multiple appearances of the same circle within a given input. Identical circles are a pain to consider, so it is a good idea to start off by sorting, then removing all duplicate circles. There is function in C++ that does this for you in $O(NlogN)$ time.

Hull, Merge and Advance

Now, lets start implementing the main part of the algorithm.

Hull and Merge

It is possible to implement a $Hull$ function and $Merge$ function seperatly. However, I just made one function that does both, as I thought it would be more fast, and also simpler. Basically, the $Merge$ function is given two parameters $s$ and $e$. This indicates that the set $S$ contains the circles $s \sim e$ in the input.

For the divide and conquer part, we simply call $Merge$ twice. When $m = \frac{s+e}{2}$, we can set $CH(P) = Merge(s,m)$ and $CH(Q) = Merge(m+1,e)$, then move on to merge the two, and return the result. This way, we can implement $Hull$ and $Merge$ in one function, which in my experience is faster as it has a smaller constant factor.

For the rest of $Merge$, you just have to implement it exactly as it is explained above. You might be wondering what to do if $L_p$ and $L_q$ are identical. The short answer is that you don’t have to worry about it. This is because even in such a case, $Advance$ is able to correctly check for bridges without issues.

Also, when intializing $L_p$, $L_q$, and $L^*$, you need to find two circles $p \in P$ and $q \in Q$ that are guaranteed to be on the convex hull. These sort of circles would be the circle who contains the highest point, or most left point, etc. I implemented it using the highest point. If $p$ and $q$ are the circles with the highest points, the that means all other circles are below it, meaning I can just initialize the angle of $L^*$ to 0, and direct $L_p$ and $L_q$ to the right. Similar methods can be used if you something like the leftmost point.

There is one tip I have when implementing $Merge$. In $Merge$, you have to repeat the loop until the convex hull $CH(S)$ is finished. The original way of doing this is by simply looping until every arc in $CH(P)$ and $CH(Q)$ have been visited.

The way I did this part is a little different. During each iteration, we add at least one circle to the hull(there are times when none is added, but thats in cases where theres like one circle, so it’s not that much of a concern), and we have proven before hand that that the size of $CH(S)$ is smaller or equal to $2N-1$. Therefore, we can just loop around $2N$ times(or a little more for safety), and it is guaranteed that the convex hull is finished. This is a lot easier to implement.

However, if we repeat for $2N$ times, there is a chance that the algorithm added the circles in the convex hull multiple times. In other words, if $CH(S) = (s_0,s_1,s_2,\cdots,s_h)$, if we repeat more than necessary the result could be something like this: $CH(S) = (s_0,s_1,s_2,\cdots,s_0,s_1,s_2,\cdots)$. Then, we need to find how much of this is the actual convex hull.

Recall when proving the size of $CH(S)$ that $u,\cdots,v,\cdots,u,\cdots,v$ is a forbidden sequence. Therefore, if such a sequence is found, it means that is where the sequence repeats, and we have found the end of the convex hull. In other words, we just have to loop through the elements of $CH(S)$ until we find some $k$ such that $s_0 = s_k$ and $s_1 = s_{k+1}$, then $k$ is the size of $CH(S)$.

A faster way would be to check if $s_0 = s_k$ and $s_1 = s_{k+1}$ is true every time we add a new element to $CH(S)$. That way, we won’t have to repeat an unecessary amount, and at the same time don’t have to waste another $O(N)$ time to find $CH(S)$.

The explanation was kind of long, but I personally found that method to be easier to implement then making sure we’ve visited every edge of $CH(P)$ and $CH(Q)$.

And that’s about it for $Hull$ and $Merge$.

Advance

The $Advance$ function is pretty simple with not much to implement. However, there are a few things you should consider when implementing.

The first one is what to set $a_1 \sim a_4$ to if $L(x,y)$ is not defined? Recall when implementing $L(p,q)$ that if $p$ and $q$ are the same, we return something large, and if a commmon support line doesn’t exist, we return somthing small. Now remember in the proof of the algorithm that the reason we check for the minimum is to check whether there is a point above $L(x,y)$ or $L(y,x)$.

The only time $x$ and $y$ can be the same is when either $CH(P)$ or $CH(Q)$ has a size of one(because we removed identical circles in the beginning). In such a case, there can’t be a point above $L(x,t)$, and therefore we just set $a_i$ to some large number so that $a_1$ and $a_4$ are guaranteed to be smaller.

A similar approach to when $L(x,y)$ is undefined can be used to determine that it’s a good idea to just set $a_i$ to some large number.

The second one is when checking for minimums. In the algorithm explanation above, I have written $a_1 = min(a_1,a_2,a_3)$. It is easy to get this wrong and think $a_1 \leq a_2$ and $a_1 \leq a_3$. However, if either one of $a_2, a_3$ are equal to $a_1$, this means that there is a point on $L(x,y)$ that is on $CH(P)$ or $CH(Q)$, just like it has been explained in the proof. Therefore you must check that $a_1$ is stictly less than $a_2$ and $a_3$. Same goes for $a_4$.

And last but not least, it is good idea to just say that $t(y,x)$ is not a bridge if $a_4$ is 0. Based on experience, there are cases where when $a_4$ is 0, something breaks. So we ignore the second if statement checking for minimum if $a_4$ is 0. We will come back to this bridge eventually while looping, so it shouldn’t cause problems.

And that’s about it for $Advance$.

Some Extra Stuff

With $Advance$ done, that is the entire algorithm explained. As an extra, you might want to find the length of the convex hull. I’m not going to go in-depth about that as it’s not really about finding the convex hull. But I will give a rough overview.

Basically, the found convex hull is oredered clock wise, with the first element being the circle that contains the highest point. There are two parts of the convex hull. Common tangent lines of two consecutive circles, and the length of arcs of circles. The first can calculated easily using the radii of the circles and the coordinats of the centers.

For the second part, you can keep track of the current angle you are at, then calculate the angle at which the common tangent line meets at the next circle. Then you can use that angle to find how much of the arc of the current circle should be added using the formula $r\theta$. It is quite simple to implement this, and I recommend trying it.

Conclusion

In this post, I have explained about an algorithm that finds the covex hulls of circle in $O(NlogN)$ time. The algorithm itself isn’t that complicated, however implementation can be bit of a nightmare if you’re not careful enough. I doubt alot of people will want to try to implement it, but I do wish some will try, as it is actually quite fun, and the code is not that long(my C++ code is about 270 lines). Of course, if you’re not careful, it can become very long(my friends C++ code is almost 1000 lines long). While it was hard, it was also very enjoyable for me to prepare such a problem, and I might do something similar again in the future. Mabye.

Oh, and if you actually did implement this and want to test it, heres a link to the problem I made: The Problem

It is in korean, but basically you’re given the number of circles $n$, then the $x$ and $y$ coordinates of the center, then the radius of the circle during the next $n$ lines, and must find the length of the convex hull of those circles. So the same problem.

And with that, thank you for reading.

Reference

D. Rappaport, “A convex hull algorithm for discs, and applications”, link

GCPC 2011, Security Zone, link

2017 East Central Regional Contest, Craters, link