I was looking for something to learn about when one of my friends recommended this topic. I looked into it and it was a lot more fun than I initially thought it was. So, here we are.

Introduction

In this post I would like to give a short explanation about linear programming and duality. While there are many topics related to linear programming, such as the simplex algorithm, and so on, here I want to mainly focus on the duality if linear programming problems, and how they can be used to solve problems. I initially also wanted to go into the simplex algorithm as well, but it was a lot harder than I first thought, so that will have to wait.

Without further ado, lets get straight into it.

Linear Programming

Linear programming is a method to achieve the best outcome(such as maximum profit or minimum cost) in a mathematical model, where the objective and restraints are represented by linear relationships.

Standard Form

The standard form is the usual and most intuitive way to describe a linear programming problem. It consists of three parts:

- A linear function to be maximized

- ex) $f(x_1,x_2) = c_1x_1+c_2x_2$

- Problem constraints like the following

- ex)

- $a_{11}x_1+a_{12}x_2 \leq b_1$

- $a_{21}x_1+a_{22}x_2 \leq b_2$

- Non-negative variables

- ex) $x_1 \geq 0$, $x_2 \geq 0$

The same problem can be written using matrices:

Find a vector $\mathbf{x}$

that maximizes $\mathbf{c^\top x}$

subject to $A\mathbf{x} \leq \mathbf{b}$

and $\mathbf{x} \geq 0$

where $\mathbf{x}$ is a vector with $n$ variables that need to be determined, $\mathbf{c}$ and $\mathbf{b}$ are given vectors, and $\mathbf{A}$ is a given matrix. The function whose value we need to maximize($\mathbf{x} \mapsto \mathbf{c^\top x}$) is called the objective function.

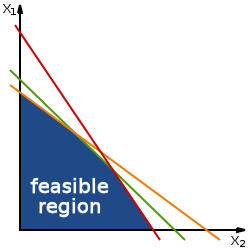

The constraints given in the problem specify a convex polytope(if there are 2 variables, a convex polygon), which is the intersection of some number of half-spaces. This convex polytope that represents the region of possible solutions is called the feasible region, and a solution inside that region is called a feasible solution.

Sometimes, a linear programming problem might not have a feasible region, when the constraints contradict themselves. In this case, we say the problem is infeasible. Also, there might be a case where the objective function can become infinitely large. Then, we say the problem is unbounded.

When it comes to linear programming problem representations, there is also something called the augmented form or slack form. This form is used in the simplex algorithm, but I’m going to spare the details since that is not int he scope of this post.

Duality

Every linear programming problem, referred to as the primal problem, can be converted into a dual problem. The way a dual problem is derived from the primal problem is by the following:

- Each variable in the primal LP becomes a constraint in the dual LP

- Each constraint in the primal LP becomes a variable in the dual LP

- The objective function is inversed, maximum in the primal becomes minimum in the dual and vice versa

In a nutshell, if the primal LP is shown as:

- Maximize $\mathbf{c^\top x}$ subject to $A\mathbf{x} \leq \mathbf{b}$, $\mathbf{x} \geq 0$

Then the dual LP will become:

- Minimize $\mathbf{b^\top x}$ subject to $A^\top\mathbf{y} \geq \mathbf{c}$, $\mathbf{y} \geq 0$

When constructing the dual problem, we are aiming to create an upper bound to the primal problem. Therefore we create a linear combination with constraints, such that the coefficients are at least $\mathbf{c^\top}$. The variable $\mathbf{y}$ are the coefficients of this linear combination. The dual LP tries to minimize this upper bound, giving the result above.

Duality Theorems

Suppose the primal and the dual LP’s are the ones mentioned before. In duality, there are two theorems.

The weak duality theorem says that, for each feasible solution $\mathbf{x}$ of the primal and each feasible solution $\mathbf{y}$ of the dual, $\mathbf{c^\top x} \leq \mathbf{b^\top y}$ is true. In other words, the objective value in each feasible solution of the dual is an upper bound to the objective value of the primal, and the objective value of the primal is a lower bound to the dual. This can be easily proven:

\[\mathbf{c^\top x} = \mathbf{x^\top c} \leq \mathbf{x^\top}(A^\top\mathbf{y}) = (\mathbf{x^\top}A^\top)\mathbf{y} = (A\mathbf{x})^\top\mathbf{y} \leq \mathbf{b^\top y}\]This theorem implies that:

- $\max{\mathbf{c^\top x}} \leq \min{\mathbf{b^\top y}}$

In addition, if the primal is unbounded then the dual has no feasible solution, and if the dual is unbounded then the primal has no feasible solution.

The strong duality theorem says that if one of the two problems has an optimal solution, so does the other one and that the bounds given by the weak duality theorem are tight. In other words:

- $\max{\mathbf{c^\top x}} = \min{\mathbf{b^\top y}}$

Basically, the optimal solution to the primal problem and the dual problem result in the same value.

This theorem has a few applications. There are two I want to talk about in this post. The first is the max-flow min-cut theorem. Basically, the dual of the max-flow problem is the min-cut problem, and because of the strong duality theorem, the two have the same solution. The second one is König’s theorem, which is similar.

Starting from the next section, we are going to be taking a look at the two.

Cases of Duality

Max-flow Min-cut Theorem

Lets start by formulating the max-flow problem as a linear program:

- variables: $f_{uv}$ $\forall (u,v) \in E$ (two variables per edge, one in each direction)

- objective: maximize $\sum_{v:(s,v)\in E}f_{sv}$ (max total flow from source)

- constraints: subject to

- $f_{uv} \leq c_{uv} \quad \forall (u,v) \in E$ (flow must be less than capacity)

- $\sum_u f_{uv} - \sum_w f_{vw} = 0 \quad v \in V \setminus {s,t}$ (flow going in a vertex must equal flow going out)

- sign constraints: $f_{uv} \geq 0 \quad \forall (u,v) \in E$

The LP for the max-flow problem is pretty straightforward. Now lets find the dual of this LP problem.

We start by creating two new variables for each constraint: $d_{uv}$ where $\forall (u,v) \in E$, and $z_v$ where $\forall v \in V \setminus {s,t}$. The reason we made the variables like this is so that we can multiply them in each constraint like so.

- $f_{uv}d_{uv} \leq c_{uv}d_{uv} \quad \forall (u,v) \in E$

- $z_v\sum_u f_{uv} - z_v\sum_w f_{vw} = 0 \quad v \in V \setminus {s,t}$

- $d_{uv} \geq 0 \quad z_v \in \mathbb{R}$

Since the direction of the inequality shouldn’t change, $d_{uv}$ should be larger or equal to 0, while that isn’t the case for $z_v$, so it can be any real number.

The primal problem was to maximize the objective function. Therefore in the dual, we would like to create an upper bound to the primal, in other words, minimize $\sum_{(u,v) \in E} c_{uv}d_{uv}$. In addition, for this to give us an upper bound, it is necessary that the sum of the coefficients of $f_{uv}$ in the constraints are at least the value of the coefficients of the objective function in the primal.

In the objective function of the primal, the coefficients of $f_{sv}$ are 1, and all others are 0. Lets start by finding the coefficient of $f_{uv}$ in the constraints where $u \ne s$ and $v \ne t$. In the first constraint, $d_{uv}$ is added. In the second constraint, $z_u$ is subtracted once when $v = u$ and $w = v$. Also, $z_v$ is added once when $v = v$ and $u = u$. Since the coefficient in the objective function is 0, we get the following constraint for the dual:

\[d_{uv} - z_u + z_v \geq 0 \quad \forall(u,v) \in E, u \ne s, v \ne t\]Lets continue for when $u = s$ and $v \ne t$. Again, $d_{sv}$ is added in the first constraint. In the second constraint, $z_v$ is added once when $u = s$. Since $v \ne s$ in the second constraint, we don’t subtract anything. This must be larger or equal to 1, because that was the coefficient in the objective function.

The same can be done for when $u \ne s$ and $v = t$. In this case, instead of adding $z_v$, we have to subtract $z_u$. Also, the coefficient in the objective function is 0 in this case. This gives us the second and third constraint for the dual.

\[d_{sv} + z_v \geq 1 \quad \forall (s,v) \in E, v \ne t\] \[d_{ut} - z_u \geq 0 \quad \forall (u,t) \in E, u \ne s\]The final case is when $u = s$ and $v = t$. In this case, the only thing added in the constraint is $d_{st}$, and since the coefficient in the objective function is 1, we get our final constraint for the dual.

\[d_{st} \geq 1 \quad \text{if} \space (s,t) \in E\]Combining everything from above, we finally get our dual LP of the max-flow problem.

- variables:

- $d_{uv} \quad \forall (u,v) \in E$

- $z_v \quad \forall v \in V \setminus {s,t}$

- objective: minimize $\sum_{(u,v) \in E} c_{uv}d_{uv}$

- constraints: subject to

- $d_{uv} - z_u + z_v \geq 0 \quad \forall(u,v) \in E, u \ne s, v \ne t$

- $d_{sv} + z_v \geq 1 \quad \forall (s,v) \in E, v \ne t$

- $d_{ut} - z_u \geq 0 \quad \forall (u,t) \in E, u \ne s$

- $d_{st} \geq 1 \quad \text{if} \space (s,t) \in E$

- sign constraints:

- $d_{uv} \geq 0 \quad \forall (u,v) \in E$

- $z_v \in \mathbb{R} \quad \forall v \in V \setminus {s,t}$

Lets take a moment think about how the solution will look like. First, note that $z_v$ is not included in the objective function, meaning we can adjust its value to our liking in order to minimize the objective function. If $z_v > 1$ then the second constraint is automatically fulfilled. However, we can achieve a better solution if $z_v = 1$ in this case, as it would still fulfill the second constraint, while allowing for a smaller $d_{uv}$ value in the third constraint. Therefore, in the optimal solution, $z_v \leq 1$ would be true. Using a similar reasoning, $z_v \geq 0$ should also be true, leaving us with $0 \leq z_v \leq 1$.

Following this fact gives us $0 \leq d_{uv} \leq 1$, as the maximum value subtracted is 1. Also, if $0 < z_v < 1$, then there would be some $d_{uv} = 1-z_v$ and some $d_{uv} = z_v$. However, based on the value of $c_{uv}$, we can set $z_v$ to 0 or 1, making the $d_{uv}$ corresponding to the smaller $c_{uv}$ into 1, and the other to 0, giving us a smaller total value. Therefore, in the optimal solution, we can think that $z_v \in {0, 1}$ and $d_{uv} \in {0,1}$. This isn’t a formal proof, which as of time I don’t know about, but more of my intuition as to why the solution would consist of only 0 and 1.

Now we know that the solution to the dual LP consists of 0 or 1. Now, we can think of the meaning of each variable depending on whether their 0 or 1. More specifically, we can think of the variables like the following.

\[d_{uv} = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if}\space u \in S \space \text{and} \space v \in T \space \text{(the edge is cut)} \\ 0, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\] \[z_{v} = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if}\space v \in S \\ 0, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]Then we can see that the objective is to minimize the capacity of the edges that are cut.

The constraints guarantee that the variables represent a legal cut.

- $d_{uv} - z_u + z_v \geq 0$ guarantee that, for non-terminal nodes $u$ and $v$, if $u \in S$ and $v \in T$ then the edge $(u,v)$ is cut.

- $d_{sv} + z_v \geq 1$ guarantee that, if $v \in T$, then the edge $(s,v)$ is cut, since $s \in S$.

- $d_{ut} - z_u \geq 0$ guarantee that, if $u \in S$, then the edge $(u,t)$ is cut, since $t \in T$.

- $d_{st} \geq 1$ guarantee that the edge $(s,t)$ is cut, if it exists.

Therefore, the entire LP describes the min-cut problem.

This has gotten quite long, but the conclusion is, that the max-flow problem and the min-cut problem are duals of each other, and by the strong duality theorem, the value of the optimal solution in the two problems are equal. Hence, the max-flow min-cut theorem.

König’s Theorem

König’s theorem says that in a bipartite graph, the size of the maximum matching and the minimum vertex cover are equal. Lets prove this using linear programming.

We start by extending the problem into that of a fractional matching. We assign a weight $[0,1]$ to each edge such that the sum of the weights connected to an edge is at most one. Similarly, we define a fractional vertex cover, where we assign a non-negative weight to each vertex, such that the sum of the weights is at least 1.

The maximum fractional matching size in a graph $G = (V,E)$ is the solution to the following LP.

- maximize $\mathbf{1}_E \cdot \mathbf{x}$

- subject to:

- $\mathbf{x} \geq \mathbf{0}_E$

- $\mathbf{A}_G \cdot \mathbf{x} \leq \mathbf{1}_V$

Here, $\mathbf{x}$ is a vector of size $|E|$ where each element represents the weight of each edge in the matching. $\mathbf{1}_E$ is a vector of $|E|$ ones, so the objective is to maximize the size of the matching. $\mathbf{0}_E$ is a vector of $|E|$ zeros, so the first constraint is the sign constraint. $\mathbf{1}_V$ is a vector of $|V|$ ones, and $\mathbf{A}_G$ is the incidence matrix, which is a matrix where each row is a vertex and column is an edge, and if the edge and vertex are connected, that cell is 1, otherwise 0. So, the third constraint says that the sum of the weights near an edge is at most 1.

Similarly, the minimum fractional vertex cover in a graph $G = (V,E)$ is the solution to the following LP.

- minimize $\mathbf{1}_V \cdot \mathbf{y}$

- subject to:

- $\mathbf{y} \geq \mathbf{0}_V$

- $\mathbf{A}_G^\top \cdot \mathbf{y} \leq \mathbf{1}_E$

Here, $\mathbf{y}$ is a vector of size $|V|$ in which each element represents the weight of the vertex in the fractional cover. The objective is to minimize the sum of the weights in the cover. The second line is the sign constraint, and the third line represents that the sum of the weights on an edge should be at most one.

Now, it is easy to see that the two LP’s are duals of each other. Therefore, by the strong duality theorem, both have the same solution. This shows that that the largest fractional matching and the minimum fractional vertex cover is equal in any graph.

However, the case of bipartite graphs are special. It is known that in the fractional matching polytope of a bipartite graph, all extreme points have integer coordinates, and that the same is true for the fractional vertex cover polytope. Therefore, all variables in the optimal solution are integers, meaning 0 or 1. Hence, in bipartite graphs, the largest matching size equals the smallest vertex cover, proving König’s theorem.

Example Problem

Here lets look at a problem where we can apply linear programming and duality to solve.

- Maximize the value $\sum_i a_i - \sum_j b_j$ when $a_i - b_j \leq c_{ij}$

Lets start by writing the LP of the problem.

- maximize $\sum_i (a_i-b_i)$

- subject to

- $a_i - b_j \leq c_{ij}$

- $a_i, \space b_i \in \mathbb{R}$

There are $2N$ variables, $a_1 \sim a_N$ and $b_1 \sim b_N$, with $N^2$ constraints for each pair of $a_i$ and $b_j$. Now lets find the dual of this problem. To do this, we simple transpose everything, and swap the objective and constraints. Also, since $a_i$ and $b_i$ are free variables, the constraints will use an equal sign. We will use a new variable $x_{ij}$.

- minimize $\sum_{i,j=1,2,\cdots,n} c_{ij}x_{ij}$

- subject to

- $\sum_i x_{ij} = 1 \quad \text{for} \space j=1,\cdots,N$

- $\sum_j -x_{ij} = -1 \quad \text{for} \space i=1,\cdots,N$

- $x_{ij} \geq 0$

We can remove the minus sign in the second constraint as well.

Lets think about a bipartite graph with $N$ vertices on one side, $N$ on the other, with $N^2$ edges connecting every pair of vertices on both sides. We can think of $c_{ij}$ as the weight of each edge, and $x_{ij}$ as some value we give to each edge. Now, we can think of each constraint saying that the sum of those values on each vertex should be 1. Then, the LP above becomes a minimum weight fractional matching problem.

However, since this is a bipartite graph, and all values in the LP are integers, the variables in the optimal solution would all be integers, just like in König’s theorem. Therefore, this simply becomes a minimum weight bipartite matching problem, where the weights are $c_{ij}$. Now, we can simply make the graph, and find the solution using a maximum flow algorithm, or something else.

Conclusion

So that concludes this post about LP and duality. Later I would like to write more about problems using duality, and also look into the simplex algorithm.

Additional Problems

Enlarge Circles (JAG Summer Camp 2018 Day 3) link : Similar to the example problem above, but with a slight twist.